In early August, 1981, I gave up a tenured professorship at the University of Michigan to move to California and start work as a “Cellar Rat” in a local winery, for $6 an hour. Fredericka and I had married on August 6th took Amtrak from Ann Arbor to San Luis Obispo, arriving just in time for one of the earliest harvests in history.

The Pinot Noir crush started during the second week of August, and I quickly learned that I had severely underestimated my fitness level. Crush work at Edna Valley in those days was extremely labor intensive; within a month I had lost fifteen pounds and gained a nice layer of callouses all over my hands. At the end of each 14-hour day I would return to our little apartment on Higuera Street ($330/month) sore and exhausted.

Regrettably, I did not keep a diary of those early days. It was abundantly clear that I could not both DO the job and also REFLECT upon it. It was one or the other. I had burnt all my bridges, and I had to succeed in my new career.

I had never been happier in my life.

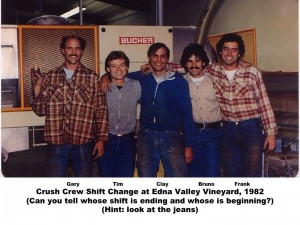

Working in the “wine business” was a breath of fresh air after the stale and stultifying atmosphere of the university. Here I found co-workers who reveled in hard work, who supported each other at all times, and whose satisfaction came from creating a product of the highest quality.

I hasten to add also that it was a heck-of-a-lot of fun. The camaraderie, the horse-play, the pranking, the unrepeatable bad jokes: there was an esprit de corps I have never experienced before or since.

In 1983, after two years of cellar work, crush and bottling, laboratory and even sales experience, it was time to take stock of my new “career.” I was never really on a track towards the title of “winemaker,” usually reserved for those who studied the subject at U.C. Davis. For a while it looked like I might be groomed to sell wine for Edna Valley and its parent, Chalone.

But what I really wanted was to make wine. Our own wine. Different, special wines. “Niche wines.”

In those days the advice was to make not wine that you liked, but that the market liked. “Make Chardonnay and Cabernet and hire a pretty girl” was the mantra.

Fredericka and I rejected this idea. Through our experience in western Germany and eastern France we had developed a love of the dry, fruity and well-structured Rieslings and Gewurztraminers of Alsace.

In the summer of 1983 we flew to Europe, took a train to the town of Barr at the northern end of the Alsatian “Route du Vin”, and back-packed southward through the vineyards and wine villages, sampling the wine and food and visiting and talking to the vintners themselves.

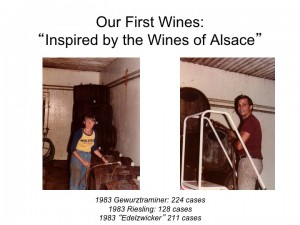

We returned eager to make wines inspired by the wines of Alsace. Still, we had no winery and no money. Happily, we were able to borrow a little from relatives, and then received permission from Chalone to start our wine production in a small corner of the cellar at Edna Valley Vineyard.

In the fall of 1983 we bought 30 used barrels and eight and a half tons of grapes and produced 563 cases of barrel-fermented, dry wines: 224 cases of Dry Gewurztraminer, 128 cases of Dry Riesling, and 211 cases of a blend of the two, which we called “Edelzwicker” after the Alsatian name.

Now we could joke that we had fulfilled our dream not only to “make wines nobody drinks” but also to “make wines nobody can pronounce.”

Next: Part III; “Selling Wines that Nobody Drinks”